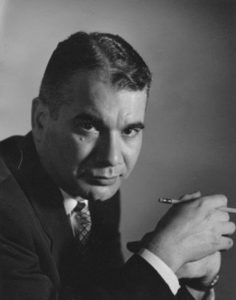

Robert Cohen

Interview with Catherine Rakow, Wednesday, June 12, 2002

Transcript (full text, 317 kb)

Dr. Cohen discusses the challenges of beginning the Clinical Center at NIMH. He remarks on the success of various people involved in studies there and reflects on his memories of Dr. Bowen’s time there.

About Dr. Cohen

In 1952, Robert A. Cohen became director of the division of clinical and behavioral research and deputy director of intramural research at the newly founded National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Cohen’s vision there was that a diverse group of patients and an interdisciplinary staff would generate research with creativity, broad thinking, and borderless explorations without the researchers having the ordinary press of funding or writing worries. And by 1970, that approach resulted in a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine being awarded to an NIMH scientist.

In 1954, Dr. Cohen hired Dr. Bowen to be part of this unique opportunity. Unparalleled and groundbreaking discoveries were the goal for researchers. And Bowen left NIMH with conviction in his nascent theory in 1959.

Prior to coming to NIMH Dr. Cohen was at Chestnut Lodge psychiatric hospital where he served as Clinical Director from 1948 to 1953. Chestnut Lodge was a major center for psychoanalysis. Dr. Cohen also served as director for the Washington Psychoanalytic Institute from 1959 to 1962 and continued working as a training analyst until his death in October 2009.

Dr. Cohen returned to Chestnut Lodge in 1981 as director of psychotherapy staying until retirement in 1991. The State Department recognized his expertise in 1980 and, in 1981, he treated Iran hostages at a U.S. Military Hospital in Germany. He spent time in retirement documenting historical facts about NIMH and Chestnut Lodge.

This interview was conducted before the formation of the Murray Bowen Archives Project. In July 2013 the interview was gifted to them for inclusion in the Oral History Project and eventual donation to the History of Science Division of the National Library of Medicine

Rakow: …For eight years I’ve been immersed in this collection of papers. I would really like now, to understand this project in the bigger picture. What was it like there at that time and (I’m) just trying to get a sense of the place. I didn’t want to go into more than that. I thought that was a lot, right there.

Cohen: What did you learn, in your discussions with Dr Brodey, and Mrs. (Basamania)

Rakow: Well, it’s been helpful to talk with them. They came to Pittsburgh and did a seminar. They actually made the project come alive, it was possible to see what they were seeing, and how it worked and they talked about things that couldn’t be known from the papers.

What was a research meeting like there? What was going on? I learned that Dr. Bowen was the one involved with the nurses. They gave more of their own observations, of what they were actually seeing. And the difficulty for them, and they both addressed this, was trying to, apparently, the way this project worked, was that the staff would be a resource to the family but the family was to figure things out for themselves. And how difficult Dr. Brodey, Mrs. Basamania both said it was, to figure out how to relate to people from that kind of a position where there was a lot of intensity and activity and exchanges among the family members in that meeting. And to be able to stay neutral to that but relate. Give them information that could be useful. So they both talked about how hard that was. And, that’s pretty much that.

The other thing, and this gets to the bottom here. That where Dr. Bowen began as an effort to extend psychoanalysis. Then this paradigm shift took place. You are not alone in saying what you said. Dr. Brodey and Mrs. Basamania have said the same thing. That they did not know where Dr. Bowen went with his ideas (in his later life) and that it wasn’t always easy to know then what was going on in his head, that he was a rather secretive guy. That was a word one of them used. And that a new theory was being formed wasn’t clear to them.

Cohen: Well. [clears throat] [Lengthy period of silence on tape]

Rakow: So I guess I’m interested in getting somewhat of a bigger picture than just this little project.

Cohen: Well, let me just say that the development of the program of the Clinical Center was really a lesson in how it should not be done. Dr. Felix came to me in the summer of 1952. I was at that time Clinical Director at Chestnut Lodge and offered me the job of Director of Clinical Research at NIMH. And I could have a very great, for those days, a very large project. They had no ideas of what the program would consist of but they were offering me the opportunity to develop that. They had a hundred beds in the clinical center, which had to be, that we were to move in by March of 1953. And that I could go anywhere in the world to see what was going on and then I could bring in, as consultants, anyone who would be interested and that we would be interested in having consult with my associates what we might do. And that my salary would be $15,000 a year which was less than I was making. That was the only thing that we had to be ready to move into the clinical center in a few months.

I wondered about it. It seemed to me that it was after all a marvelous opportunity, and it seemed to me socially, it was very desirable. I thought it was very important, that there was a grave need for mental health, the state hospitals were full of patients being very poorly treated. But at the same time, it seemed to me, that, how does one start a program from zero and move in to a new hospital with a hundred beds and find people who would come for a salary even lower than mine.

So, I turned it down after a lot of anxiety of thinking about it and talking to people, finding whether they’d be interested in coming. The McCarthy hearings were past by that time, but still, people generally weren’t eager to come and work for the government. And so, I turned it down but obviously I was so conflicted in doing it that Dr. Felix came back several weeks later, and said “Well now have you thought some more and wanted to reconsider?”

Rakow: Maybe he knew a good man when he saw one.

Cohen: Well I agreed, considered it, I thought that well, it might not be starting under the worst conditions, but at least it was worth trying. That there wouldn’t be another opportunity like this in the whole wide world. And I didn’t decide- didn’t really begin to until November of 1952. There were a lot of people- I had been in the Navy, I’d been called to active duty before the war started and so I completed military service. There were a lot of people who had not served in the military during the war. And so I went to some of them and said, “Well, if you’re called up, in this Korean conflict, would you come?” And several very experienced senior psychiatrists who were professors at various places said, “Well, in that case” they’d come. And so I figured, well, they wrote out applications for appointment at the public health service. And then President Eisenhower went and brought the Korean War to a close. So they called up and gave me their best wishes and said they weren’t interested.

Rakow: Oh dear.

Cohen: And, the only way it looked that I could get going, was to accept people who had not been in the service during the war and weren’t being called up. There were a lot of people who were second or third year residents who applied. I figured that I could select from those. The ones who would at least get it started.

Rakow: How did you get the word out?

Cohen: Well, well, it was published widely so if we heard from people-

Rakow: So, you began November of ‘52.

Cohen: I had not started; I had an appointment before I came up on active duty, actually, on December 30th of 1952 with no staff except one. I had talked to Dr. Fritz Reidl, have you ever heard of him?

Rakow: His name has shown up, in…Yes, he had a project with children.

Cohen: He was a distinguished professor, actually, at Wayne State. He’s not a physician, but he had been a student of- he had been a graduate of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. He was a colleague of Erik Erikson, you’ve heard of him. And, a student of Aichhorn, who had written the war book Wayward Youth, and he and Reidl had written several books on the treatment of hyperactive, aggressive, anti-social children. And I thought to myself that I wanted to have several groups of patients that we would have one group of these hyperactive children, and we would have another group of patients who had disorders of thought or affect, that is, schizophrenia, or emotional disorders, depression, elation. And another group who had psychosomatic disorders. I was thinking these are three groups in which there would be sharp contrasts, some patient who reacted to whatever it was, stress or heredity and what have you, with anti-social behavior, others who reacted with disorder of thought or affect, and others who reacted by bodily function disorder.

And I have a PhD in physiology, as did my wife, and then we both had gone into psychiatry after medical school. So that I had the background in the biological sciences although I hadn’t done anything in that after graduate school nor did my wife. We had both done psychoanalytic training. So, in addition to actually having psychiatrists working with patients, primarily because of other experiences, I wanted to have a group of psychologists. When I was a resident at Phipps Clinic, they had two psychologists, one was at the Sheppard-Pratt Hospital, and one psychologist, he happened to be the Dean of Johns Hopkins, so he was no ordinary one. And then when I went and spent a year at the Institute for Juvenile Research, where they had social workers and psychologists and psychiatrists working together. So I got to know something about sociology, so I wanted sociology represented. As well as psychology, as well as physiology, biochemistry, and which is a very big area that I was looking for. And then I

Rakow: Very diverse!

Cohen: [silence] When I actually reported- I didn’t even have these experienced psychiatrists who now no longer were being called up, but I was bombarded by second or third year residents in psychiatry who would rather be in the public health service than in the Army or the Navy.

And among those who came, was Louis Cholden, who was from Menninger’s, and he said that he knew Murray Bowen from Menninger’s and he called and spoke to him, and so Bowen applied. And this whole group then got together and from the very first, I anticipated – I was particularly interested in them, in Cholden and Bowen, because both my wife and I had worked in Chestnut Lodge and they at Menninger’s, where the patients were essentially the same. And we, all four of us, plus some others, were interested in family, and had a somewhat the same theoretical approach to patients. And so I thought that this would- I thought there would be considerable interaction. And that was how things got started.

Rakow: Well, I wondered how he came to be there.

Cohen: There was a very strong interest in the family coming from psychoanalysis, how could there not be? So for example, Julianna Day and Irving Ryckoff, one of them would treat the mother and the other would treat the child. And Dr. Lyman Wynne, who came, he had come from Harvard, and was a graduate student in sociology as well as a medical school course. He was working for his PhD, so he was very much interested in the family. All of the people in Reidl’s program, he was the first laboratory chief of the program, were very much interested in the background of these children. And so there was a welter of individual studies and meanwhile I was looking for senior people to come in who would be the center. In other words, one of the reasons I had rejected the appointment at first because it seemed to me you’re going to go in there backwards rather than forwards. The normal thing would be to get several people who were senior people who would gather around them the juniors. And who would determine the course of things. And we were developing it the wrong way but in the end, I thought, well, better than nothing.

Rakow: Well, it certainly speaks to this whole body of knowledge came from that time and what was going on there and the ability to-

Cohen: It turned out to be very successful, but I don’t think it was the way to do it, if you will. Johns Hopkins University, I’ve, as a high school student, I’d read the Cushing’s Life of Sir William Osler, and that had been the thing I was working toward. Well, Johns Hopkins got started, the medical school, which was the most famous, one of the more famous ones, in the world. They got the four professors together, they determined what they were going to do, and they brought it in. And if Dr. Felix had offered me that at the beginning and said, “You have two years to do it” I wouldn’t have even hesitated. On the other hand, I don’t know why he would have offered it to me because although I had a PhD in physiology and though I was a training analyst, et cetera, I actually hadn’t done research.

Rakow: Well, there must have been something he knew about you?

Cohen: Well, [laughter] I do know a great deal about what was going on. And, and that was how it got started. Now Dr. Bowen, [silence] various things got started that were quite remarkable in a way. That is, Dr. Wynne completed his PhD and, in sociology from Harvard, and then completed analytic training. He had a particular interest in the family. Then, Margaret Thaler Singer came and worked with him. She was a very remarkable young psychologist. They had a very large project on the family going on. And Margaret Singer developed a, she was able to take a group Rorschach and grouped the families together and say, “This comes from this family; this person comes from that family.”

Rakow: Is that right? She could tell-

Cohen: Even without seeing the people, and even without even much, because we were doing family studies in Denmark. She could do it with just the records. They were (inaudible).

Rakow: She could tell who belonged together.

Cohen: Yes. And it was not, it was related to a kind of thinking that she knew that it was a rather uncanny thing. And they published paper after paper and it was regarded as a very interesting program. They didn’t think that that meant that the patient’s illness, if you will, was due to the experience of the family. It might be that the reaction of the family as a whole to the illness developing

Rakow: And that’s a very different, it’s a different thought.

Cohen: It’s a very, very different conception. And this became a very major study of the program. Then another thing that happened one day, is that I got a telephone call from a doctor in Lansing, Michigan, saying that they had a family of four schizophrenic girls, identical quadruplets

Rakow: I’ve read some sessions of those.

Cohen: Yeah. And we sent Mrs. Basamania and Dr. Perlin went out to Lansing, and met the family and the doctor and found out that these were identical quadruplets. And called us up and said, “the family as a whole are willing to come into the clinical center.” And the fantastic thing about what we did have was that we could say, “Well, just bring them in.” And they lived in the clinical center for three years.

Rakow: And I know for a while they were on the ward where Dr. Bowen’s project was. They came and went. I know they were there for a couple months.

Cohen: They lived in the hospital for three years and during that time, we set up a number of projects. Each patients was seen by in intensive therapy by one of the doctors and Dr. Bowen was one of them.

Rakow: And I’ve read those sessions. Those are part of the archives. So I do know those.

Cohen: And in addition each person was supervised by a senior psychoanalyst who (inaudible) And then, in addition to that, each week, Dr., a very senior psychoanalyst, came in to meet with the therapist. And Dr. Bowen became very attached to that doctor.

Rakow: Is that Dr. Hill? Was that Dr. Lewis Hill?

Cohen: Dr. Lewis Hill.

Rakow: I know that in the records it indicates that Dr. Lewis Hill was a consultant to Dr. Bowen’s project.

Cohen: Well, [laughter] was a consultant to Dr. Bowen.

Rakow: Okay, he was a consultant to Dr. Bowen. There’s a difference. Alright.

Cohen: He was a consultant to all four of the doctors he was seeing. In other words, Dr. Bowen’s work was part of that. And when Dr. Rosenthal wrote that – did you read the Genain Quadruplets book?

Rakow: No no, is there- I would like-

Cohen: That’s published-

Rakow: I wonder what happened with those girls.

Cohen: Well, you can look that up. Unfortunately, I loaned my copy to someone

Rakow: Could you spell Genain to me?

Cohen: G-E-N-A-I-N. Dr. David Rosenthal was the overall integrator of that entire project.

Rakow: And it’s Genain quadruplets?

Cohen: Yeah. The- Genain was a name he invented, Dr. Rosenthal invented. And I’m sorry that I can’t give you the-

Rakow: Oh, that’s alright.

Cohen: But you can undoubtedly find it.

Rakow: I’m good at finding old books. I think I came naturally to work in libraries!

Cohen: Dr Rosenthal was the one who integrated everything being done. And Dr. Perlin’s report of his work with his patient, his patient actually made the most progress.

Rakow: Well I know Dr. Bowen didn’t work with this young woman very long. It was maybe 8 months or something.

Cohen: Well, the only reason he didn’t is because she wasn’t responding terribly well.

Rakow: Oh I see, okay.

Cohen: It was his decision, not

Rakow: I know he transferred her to somebody, I don’t remember who. But there is a transfer note, and it’s in there that you can get some of the…One of the things I’ve tried to do Dr. Cohen is to be accurate and only represent what I have evidence for… Sometimes I read things in, but- always keep separate what’s in my head and what there’s evidence for. And there’s a transfer note where it is possible to see some thinking of Dr. Bowen’s where he describes the sisters as being two sets of two and being on a seesaw where this set functioned higher than this set. But within each set there was a dependency and then the fulcrum was the mother.

Cohen: Well each- each person- it was a group project- and no one of them was the leader. Actually, Dr. Rosenthal picked Dr. Perlin’s report as being one that he included in the book.

Rakow: Well this is just a handwritten transfer note but it’s one of the few places you can see what he was thinking.

Cohen: Oh, oh, that’s right, that’s right. Now, then Dr. Bowen began working later with Dr. Dysinger.

Rakow: That’s a question I have. On the individual project report for December of that first year, it lists other investigators on Dr. Bowen’s project. Lyman Wynne and Irving Rykoff

Cohen: Well, Lyman Wynne was senior to Dr. Bowen. So Lyman Wynne was involved in that project.

Rakow: But then they don’t show up after that, after December of ’54 they’re not on there.

Cohen: They- they don’t [laughter] – In effect, I think, well let’s advance further. The- I think that if- Finally, [silence] I hadn’t appointed a senior person to that whole group until finally David Hamburg was appointed in 1958. So things had gone along and during that time, and-

Rakow: So, when you say, “that whole group,” you mean the Family Studies group?

Cohen: He would be in top of the adult psychiatry, in other words the Family Studies were part of that, Lyman Wynne and studies of that. And many others, because in addition to that, we had people from sociology that were involved. In other words, you can get some idea by going through Dr. Rosenthal’s book of the number of people who were involved. Now, you could say each person was doing his own – and that’s true, but it-,

Rakow: Well, there had to be some integration, exchange of information.

Cohen: Well, yeah, but no one of them, as it were, was directing each of the others. They could work individually as partn- and trying to move as it were

Rakow: I know there’s a name, I think it’s Charlotte Schwartz, that comes up.

Cohen: That’s Morris Schwartz’ wife. And she used to do work at- at- well, she

Rakow: Is she a sociologist?

Cohen: She’s a sociologist.

Rakow: That’s what I thought. Cause there’s some materials that have her name on, and I knew she was doing some observation. Okay. I think she might have been a silent observer perhaps at the meetings.

Cohen: At the time she might have been. She was originally Charlotte Green. She originally worked at Chestnut Lodge and she might have been a consultant. The organization, by and large, was relatively loose, but the group, most of the group, that were in either the adult psychiatry branch, the psychiatrists, or in sociology, and psychology, and Dr. Rosenthal was the one who tried to draw from each of them the contributions that they were making to the project.

Rakow: Well that’s a question-

Cohen: And Dr. Rosenthal, also, that became a focus of these studies on genetic transmission of schizophrenia, as opposed to the social, psychological transmission, if you will. And so Dr. Rosenthal and Dr. Ketty and Dr. Bender began looking for the genetic, to see if they could prove that genetics played a role as opposed to the experience.

Rakow: Well, they’re still trying to figure that out!

Cohen: And so, this was a total structure with all the things going on. Now one of the things I would say about Dr. Bowen was that he kept his – he didn’t participate in the group process as much as the others. That is, I don’t think that I ever knew as much about what he was thinking. Because his pap – he kept careful notes, et cetera, but he didn’t produce so many and didn’t take part in the discussions. When Dr. David Hamburg came to be now the chief of the laboratory in which all the psychiatrists were working, he was faced with a problem in which Dr. Bowen was doing family studies, Dr. Wynne, and Dr. (inaudible), were- had already turned out reams of papers which were very impressive and were going on. He also had wanted to have some other studies, which were going on at the same time on biological studies of schizophrenia, et cetera. Dr. William Bunney, [silence]

Rakow: That’s one of the things I looked at Dr. Cohen because I found an individual project report that listed publications. It got very clear to me that there was a lot of publishing going on, and Bowen’s was limited. I did it for ’57, ’58, and ’59, and so I was wondering how much of a problem that was presenting. The little asterisk means publications. [Showing him papers]

Cohen: Yeah. Well, these were all people who were very active in the program.

Rakow: So I pulled that out to look at that. Because that was one of the things that Dr. Brodey had said was the fact that there weren’t publications coming out of this was a problem.

Cohen: Well, what happened then, in the end, was that Dr. Hamburg in reviewing all of the work in the lab felt that, although it was good, there was too much related to the family. And he wanted to bring in some more biological studies to the program.

Rakow: And he came in ’58?

Cohen: He felt that he didn’t want to continue with Murray’s program. Which, at that time, that is, he was contrasting the amount- the number of papers, and –

Rakow: And the amount of money, I’m sure. Spent on that program.

Cohen: And, so he felt that he would not want to continue supporting Murray’s following out his own line of research. He wasn’t criticizing him, negative- he felt that the others were being more productive.

Rakow: No, I understand these decisions are made based on many factors.

Cohen: And, Murray, instead of, quite naturally, feeling that well he’d want to pursue his own ideas not to participate in the development of group projects. And as I look back on it, Murray is the only one who’s had a program named for him. Dr. Wynne, well, Dr. Hamburg himself, later left to go become Chairman and Professor of Psychiatry at Stanford, and after that he became the President of the Institute in Madison. And after that he became professor at Harvard, and after that he became the President of the Carnegie Foundation. And Dr. Wynne ultimately became Chief of that laboratory after Dr. Hamburg.

Rakow: Oh, is that right?

Cohen: Then he left to become Professor and Chairman at the University of Rochester. There were two other doctors there, Dr. Strauss and Dr. Carpenter, who not only took part in some of the studies going on there, but they worked with (T. Y.) Lin, who was at the World Health Organization, studying families of schizophrenics in other cultures, And they found, for example, that even though schizophrenics seem to have the same symptoms, that schizophrenia was a milder disease in some of the less advanced countries with a different kind of family setting. Well Dr. Strauss became a professor at Yale and Dr. Carpenter is the Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at Maryland and has won all sorts of awards. And in that sense the program was a great success. But I think it was in that setting that I’ve been very interested that Murray, in a way, benefited, I think, from being pushed out of the job. Although, he conceivable he might have developed it. I personally was, I must confess, somewhat disappointed,

Rakow: It’s an interesting question.

Cohen: because I had expected that I would have much more interaction with him because we had both been struggling with treating the same kinds of patients. And, he at Menninger, and Cholden was a much more outgoing person in that sense. Murray really didn’t [silence] I was surprised, and not surprised, that is, because I felt like he wouldn’t have been there if I hadn’t been impressed by him personally, not by his setting. But I was disappointed that he kept his thinking, he was writing it out, and relating it, while others were giving more people a chance to interact with them.

Rakow: Well now, I have thought a lot about that Dr. Cohen. And I have wondered, because I was never trained in psychoanalysis, but the way I understand this, is that Dr. Bowen was faced with information that didn’t fit in what his training. And what do you do with that?

Cohen: Well, what you do with it in that sort of setting is report on it to the group, get them involved in and throwing it back and forth. That’s- and Murray didn’t do-

Rakow: Yes, I hear that.

Cohen: if Murray had done more of that, I think he probably would’ve-[silence] Well, it was a personal matter and I think that Dr. Hamburg made a judgment which was not unreasonable. But at the same time, and in a sense it may have been the thing that made Murray realize, “Well, I’ve got to share some of this with others.”

Rakow: It’s an interesting point, I think. Dr. Kerr wrote a book in 1988 and Dr. Bowen wrote the epilogue to it, which was his effort to give a narrative of his places where he was and his thinking as it developed. And in there he says that he fashioned, I think this is pretty close to a direct quote, he fashioned a systems theory while at Menninger’s. Now, my thinking, then, is that I ought to be able to see some of this somewhere in here. He also- now, that’s 1988, that’s forty years later. He’s writing this. But it does seem to me from what’s in this project that what he’s talking about as a systems idea is not separate from psychoanalysis. Which is what happened with this research. And I don’t know how a person when faced with that, what kind of confidence in yourself you’d have to have to go into unknown territory to create a new theory. I think the natural thing would be to somehow stay within the accepted model. So, it’s a question to me about what what was going on in his thinking, when, and how can it be documented. But also, would there have been something lost to have put it out to others. Did he need to get more conviction about it? That’s speculative. I don’t know. But these are questions I have. I can certainly see in the clinical materials and in what writings there are the basis for where he stepped off in the creation of a new theory. [Silence] And it’s an interesting question. Would he have continued, I suspect he would have, had he stayed at NIMH? Or did, as you suggest, it spur him?

Cohen: Well, he might have.

Rakow: Perhaps it spurred him! You’re suggesting it did.

Cohen: Well, it seems to me that, I don’t know, if I – I wouldn’t put, that’s a problem for a research director, always. When you’re making a choice between people, [silence], in terms of [silence] I don’t know whether Bowen- whether he would’ve flourished as much, if he had stayed at NIMH. On the other hand, I think it’s quite possible that he might have.

Rakow: We can’t answer that, that’s an unanswerable question.

Cohen: Because how can you say that, that would be assuming a vision that I don’t think I ever had.

Rakow: But you know that having whole families there is such a remarkable operation to have the whole families there. And he’s very clear; he says that outpatient families often did better than the inpatient ones but that his principles came from the inpatient research. And it’s a question for me, had he stayed would there have been new knowledge that would have been gained from that kind of opportunity, that 24 hour a day observation. Now the question I have about the material I’m looking at, one part of me wants to simply say, “This is how it worked, this is how the project operated.” That’s the easy part. The part that interests me a little more is to say, “What else is there that could be developed?” Because I think the material can be mined to add to knowledge.

Cohen: Well, after I left, the interest in the intramural program, shifted.

Rakow: When did you leave?

Cohen: I was there for 29 years.

Rakow: Quite an accomplishment for someone who didn’t want to go [there in the first place. Addendum 9 Aug 2017, CMR].

Cohen: One of the first things, that Dr. Goodwin did was to tell, he cut back on the sociology and cut back on the psychology and increased the biological stuff. And, so that the kind of interest that- [silence [ today, it seems to me, I still think that behavior is governed partly by heredity and biology. It’s expressed by physiological processes but I can’t feel that life experience didn’t play a tremendous role in the in the development of the person. And yet the treatment, now is, it is The Brave New World where they give pills, rather than inter-personal contact. When I was- and my late wife were analyzed, senior people who were analyzed by Dr. Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, Lewis Hill was our teacher. They charged us $7 an hour, with $3 down and $4 on account. Doctors don’t do that anymore.

Rakow: I hear you.

Cohen: And they saw us at 7 o’clock at night because we were working during the day. Now… [Silence] I think someday they will net the biology and psychology together.

Rakow: Well, when I started at the Mental Health Center, I started there in 1982 – I’m a late bloomer, I didn’t go into a profession until my late 30s. I had my family first and then I went into professional work. And, in 1982, at the Mental Health Center, when someone would come in they would be told, “You’re going to start with some therapy, and then as time goes on, if you need a little help with some medicine we can try that. But let’s do this first.” And when I left in 1997, people were coming in saying, “I need Prozac.” They were asking for medications. Or they were being told, “Let’s try the medication. And then if you think you want some therapy, we’ll try that.” So it had completely reversed. The emphasis was completely different just in those 15 years. But, let me go back to this kind of inwardness of Bowen’s. How was that received by others there? Were they wanting to know what he was thinking, or-?

Cohen: Well, let’s put it this way, in that sort of setting we wouldn’t chase him and hold him down and say, “Tell us!” He had, every opportunity in the world and he was working with people who used these opportunities, Lewis Cholden, who died very early because he was killed in a,

Rakow: Yes, car accident.

Cohen: taxi cab accident. He left the program, because he got a fabulous offer from someone in Los Angeles.

Rakow: So he died after leaving the program?

Cohen: He died on his way to the airport to come to a psychiatric meeting where he was going to present a paper. When Lewis Cholden presented papers, he spoke to a meeting of all the institutes that we had a case conference (inaudible) by doctors, all the institutes. He indicated he wanted to and we were looking for people to do it. We weren’t going to ask someone to do it if he didn’t want to. In other words, Murray, I think felt he developed it the way he developed it. He did his thinking interacting with some people not necessarily with others. He was very attached to Lewis Hill, which both my wife and I were, because he was the first supervisor that we had.

Rakow: That comes over in his writings. He even kept the eulogy by Sarah Tower. That’s part of the collection. He kept that. That’s quite impressive.

Cohen: Sarah Tower, as both my wife and I have degrees in physiology, and Sarah Tower was ahead of us at, she was a senior student in the Department of Physiology, when we were just starting, for our doctorates.

Rakow: And he referenced it in so many letter that I started hunting for it. I finally found it. Mrs. Bowen [loaned] the NIMH papers but I found it at her home. There’s a whole lot of papers at her home. But the other thing, and I’m not sure how this worked in the larger system, is Dr. Brodey, when he was here in Pittsburgh, he was saying that the families generated a ruckus in the building. He said one family, as they’d go up the elevator, it would start on the next floor, and the next it would start there. That as they went up each floor, they created a ruckus. And, that has to have some impact at the larger system too. That these families seem-

Cohen: Well, it was five laboratories got involved with it. And Dr. Rosenthal, who died tragically because he got a very fulminating Alzheimer’s, and in the end didn’t even recognize his wife and children. It was just heartbreaking. He was such a brilliant and such a sensitive person and that book, I always reacted to it with just, emotionally, because he dedicated it to four people who died too soon, he said, including his father, but, three colleagues who died early, and he was such a remarkable, sensitive and gifted psychologist.

Rakow: Well, it certainly sounds like this was a rich place to be.

Cohen: Oh it was Rakow: Could there have been a better place to be at that time? I’m listening to you and I’m thinking that, perhaps, your approach is what allowed this kind of freedom in there. That you wanted this diversity, you wanted the disciplines to be represented. And that contributed to the richness. And certainly Bowen’s project, which has gone on, you say he’s the only one with a Center named after him, but he may be the only one with a theory named after him too that is increasingly recognized worldwide-

Cohen: I was very interested in –

Rakow: and the work that he did there-

Cohen: Well, I have to go, my hearing aid that I-

Rakow: Okay. Alright. Thank you so much.