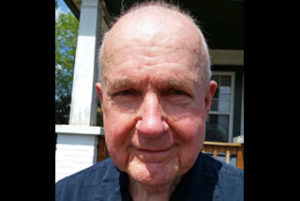

Jay Combs

Interview with Andrea Schara, Sunday, April 14, 2013

Transcript (full text, 349 kb)

Mr. Combs spent his career in administration in public agencies: first, as mainly a supervisor in child welfare in a large suburban county in Maryland (Prince George’s) for about 15 years and, later, for about 15 years as a director of a social services department in a small, rural county (Caroline) on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. His knowledge of Bowen Theory was gained mainly through regular attendance of the Wednesday Theory Meeting for 18 years under Murray Bowen and over 20 years under Michael Kerr. As he states, “what amazes me is Bowen’s effort at defining as concepts processes driven by the emotional system. It’s been two generations since the NIMH project, and, still, no one has come close to this.”

About Mr. Combs

My background is different than most in the Bowen network in that I, a non-clinician, spent my career in administration in public agencies: first, as mainly a supervisor in child welfare in a large suburban county in Maryland (Prince George’s) for about 15 years and, later, for about 15 years as a director of a social services department in a small, rural county (Caroline) on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Also, I did not attend the Bowen Center graduate program: my knowledge of Bowen Theory was gained mainly through regular attendance of the Wednesday Theory Meeting for 18 years under Murray Bowen and over 20 years undder Michael Kerr. I’ve been familiar with the Theory for about 45 years.

As the years pass I, as with so many others in the Bowen network, am increasingly impressed by how new scientific findings are supporting what Murray Bowen theorized decades earlier mainly by observing and thinking about human behavior. But what amazes me is Bowen’s effort at defining as concepts processes driven by the emotional system. It’s been two generations since the NIMH project, and, still, no one has come close to this.

For the Murray Bowen Archives Project of Leaders for Tomorrow at History of Science Division of the National Library of Medicine

Note: As you read this transcript, there are places where Mr. Combs made insertions as he edited it. Those places are marked [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017:_insertion]

Unnamed Speaker: Sunday, April the 14th, with Jay Combs.

Schara: [silence] I don’t- I get so confused about which things to sign, on these things, but… [silence, quiet murmuring, sounds of writing] Is the ‘interviewer’ the person you’re interviewing?

Unnamed Speaker: No, that’s you. You’re the interviewer.

Schara: Oh, I’m that. So I have to sign all of this whole thing myself. Eighteen times, at least.

Unnamed Speaker: Sign that eighteen times!

Schara: Lordy. [silence]

Combs: I’ll put my cell phone down. I keep it turned off. You’d never be able to reach me. [silence]

Schara: Alright. So I’ll just keep this on, so we can try to see how far we get in an hour. We can always do more, but today is the 14th, beautiful 14th of April, it’s a beautiful day, and Jay Combs, delighted to be able to spend an hour with you and talk about

Combs: You’ll be bored to tears! [laughter]

Schara: Well, then I’m looking forward to being bored to tears! [laughter] If that’s what you’re up to.

Combs: I’ll try not to, but I- but I ooze boredom. [laughter]

Schara: Except when you laugh.

Combs: Well, that- that’s true, maybe not. You may be on to something.

Schara: And uh…so, the first question there, nine questions, in all, and I see you’ve written some notes, here.

Combs: I’ve written down your questions.

Schara: Alright.

Combs: And ah, ah, “Who am I?”

Schara: Yes, “Who are you?” And how did you come to know Dr. Bowen? Yup.

Combs: Ok, the tape is on and running, is that correct?

Schara: Tape’s on and running as far as I can see. Yeah.

Combs: Alright, I’m- I’m Jay Combs. I knew Dr. Bowen for eighteen years, beginning in 1972. A little background: I got my Masters in Social Work from Howard in 1968. And I had an ongoing interest at that time, from ’68 to, oh, through ’70, in family therapy. I was very interested in it. I got a taste of it at Howard, and a taste of systems, with Bertalanffy [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: Ludwig von Bertalanffy], and I really thought that was the relevant way to go in the field. I first saw Dr. Bowen in 1970. Because of that interest I attended all the conferences, and I attended an Ortho conference here in DC, in 1970- spring of ’70.

And there was a family therapy panel with Virginia Satir, Normal Paul, and, and Murray Bowen. There might have been someone else, but it was mainly Virginia Satir, and Norman Paul that I went to hear. I knew about them, I had read Virginia Satir’s book, and I had probably read an article or two by Norman Paul, and seen him on TV, and was very interested in family therapy. And Murray Bowen happened to be on the panel. And he just sat there, smoking cigarettes, and this was 1970. And I have a story to tell you about that; I’ll tell you in a moment, about cigarette smoking, But, of course, if you remember Virginia Satir, she dominated the panel. She was, you know, very good, very insightful, flamboyant, and she did most of the talking. And it was very interesting, Norman Paul, too. And Murray Bowen didn’t say much, he just kind of sat there, smoking cigarettes. And not smiling, looking serious. And what struck me about Bowen was a question, his response to a question, toward the end of the panel that someone in the audience asked.. A young guy, a social worker of course, or in the helping field, And he asked a question: “Aren’t communes really, a form of family?”

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: If you remember, this was 1970, it was still the late-60s mentality. And communes were still a big thing. And the guy asked, “Isn’t a commune more or less like a family, a kind of family, and can’t you do many of the things you would do in your own family in a commune?” And Bowen was very direct, and said, “No, it’s not. It’s not a family.” He said, “In fact,”, it’s a form of running away from- -it’s a cutoff from the family.” This was very out of sync with the times. And it struck me, also struck me as very sensible, because while I had an unformed idea of all the communal stuff, I suspected, I just sensed it was a, a form of running away, of just distancing, although I didn’t know that term, distancing, at that time. His response sounded very sensible, and stayed with me, obviously; and yet I came away from the meeting thinking two things: That his response was very sensible, but that he was smoking.

Schara: [laughter] Which wasn’t sensible.

Combs: Which was a negative– I happened at that time to have just quit smoking, after years and years. I started as a teenager, and I was a habitual smoker for probably close to fifteen years. And it was one of the hardest, probably the hardest thing I had done, up to that time was to quit smoking. And one reason I quit was that I saw smoking as a very negative, addictive behavior. Especially with someone in a, in a helping field, that was giving, trying to give guidance to other people!

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: And here I was, with this major flaw, this addiction, that I could not control. And so I had a very negative view of it. At that time, keep in mind, this was 1970, and I had a very conventional view of symptoms. It was a static view. I saw symptoms in a static way, with no relation to levels of anxiety and self. I had no concept of Bowen Theory. I saw a person with a symptom, as symptomatic, and without any idea of level of differentiation, or anxiety, anything like that. And so I came away with a positive and negative view of Murray Bowen, as someone who was perceptive and also who had this addictive behavior, and why would anybody who was in the field and, and trying to help other people, have this addiction? Also, a little background: at this time, I was in a several year period, probably almost three years, of analysis. I had entered analysis in ’69. And I, even though I’d been fairly involved in it (until ’72,) and even though I entered it because I clearly saw the need, in myself, to try to understand myself better, to try to understand human behavior better, yet I had no view of analysis as science. In fact, I would tell my analyst that, “hey, this is not science.” I saw it as an open system, that provided a lot of support. It’s easy to get addicted to, it’s very open, and it provides a lot of relief. But the more I got into it, the more I saw that action was necessary. Talking is just not an effective course.. It’s an open system, is beneficial, and you can get benefit from it, as I did. I got benefit from analysis, but it doesn’t lead, I think, to much change. It’s not science. You need action. And that’s where I was at that time. In 1971, over a year after I had first seen Bowen at the Ortho Conference, a colleague of mine brought me paper by Bowen. Her name was Isobel Phillips, and she was the wife of Paul Phillips, who was a good friend of Dr. Bowen. Close friend. And she brought me his major paper, Defining a Self in Family, because she knew me, and she knew I was interested in family therapy. This was in the fall, I believe, of ’71, 1971. And I read it, and, like a lot of people, I was just blown away– I thought it was unlike anything I had read. And defining a self, going back into one’s family, just made so much sense to me. I realized, especially from my analysis experience, that action was required, and really, family of origin was where you needed to go. It was where it began.

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: I didn’t want to go there, but it was where one should go. And needed to go. And so I was really impressed by the paper. And then a couple of months later, I met her husband, Paul Phillips, at a cocktail party, I told him how impressed I was with Bowen’s paper, and he said “Well, Murray Bowen has this this regular theory meeting, every week, down at Georgetown.” He said, “It’s open to anybody. You can go down there and attend it.” And he told me where it was, and he said, “If there’s any, if anyone says anything, just tell them that Paul Phillips told you about the meeting.” (inaudible) [laughter]

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: So I went down there a few weeks later. It. was the spring of 1972, and I went down to the Wednesday theory meeting–an hour and a half meeting–, and sat through it, and at the end I went up to Dr. Bowen, and I said, “Dr. Bowen, I’m Jay Combs, I heard about this meeting, I’m interested in family therapy,” and I said Paul Phillips told me about it, and he just looked at me, looked right straight in my eye, with that look of his, and said, “Okay”. And that was my first contact [laughter] with Murray Bowen. And at that first meeting, he said things, again, that just I just knew that this was where I wanted to be, to attend. One of the things, he mentioned, was that he was factual, about theory, which he emphasized. Somebody asked a question and his response was, “What principle of human behavior are you basing that on?” [laughter] And that was the first time I’d heard anything like that. It has stuck with me forever. “What principle of human behavior. . . “- And I thought to myself, “God, I’m glad he didn’t ask me that question.” Because I was moved, usually moved, by so many feelings, feeling responses. And he said other things. factual things. Anyway, from then on– it was an the spring of 1972– I attended regularly, until his death in the fall of 1990. The- the meetings were weekly, until I believe, oh, the late 70s, and or maybe until close to 1980, and then they became bimonthly.

Schara: In 1980 they became bi-monthly? I couldn’t remember when.

Combs: Well, I- I’m not sure. Of the, of the date. Sometime in the . . . .

Schara: Yeah, sometime in the 80s. I came, in 1980, to work there. And had been in the post-graduate in 1976.

Combs: Were they bimonthly when you came?

Schara: I think s- I think they were weekly for awhile, and then they became. But yeah, I’m not sure

Combs: Right around that time. And they- and they were always, in the

Schara: Yeah, right around that time. Ruth would know.

Combs: early years, focused on defining self and the family. And later some work systems stuff; and in the late-1970s it became more about societal emotional process. Around 1980 or so he actually said, “Well, I’d like to focus more on societal emotional process.” But there was never any real rigid rule–if someone wanted to talk about family they could. Also, by the time I really got into attending the theory meetings my interests had shifted from family therapy to administration. I’d decided that administration was where I wanted to go, I did not want to be a clinician. I don’t know the reason, you know, you can only speculate. But I had shifted, I was clear in my mind. I wanted to go into administration. But that didn’t keep me from wanting to know the theory. My motive for attending the theory meetings has always been wanting to gain knowledge for myself, of human behavior, for me. I was less interested in applying it clinically. I wanted to understand the human phenomenon better and have a knowledge of the environment and the world that I thought was more valid. But I was always interested in focusing on self. I didn’t communicate it much at work. People knew my involvement, but I didn’t try to convert anybody. But I did apply it. And I have always had conflict and problems as a result of that, because I’ve always worked in public agencies, where I had to implement public policy that affects people’s lives. When I first attended the Bowen theory meetings I was a supervisor in child welfare and later an administrator of a department. I directed a department. I’ve always had to administer public policies, and I it’s always been my assumption that when one has to do this, one comes more into conflict with the larger societal network than you would as a clinician in, say, a private organization. At least, that’s been my view- I’ve always had problems. And Bowen Theory has been very helpful in helping me negotiate through them. I survived, I retired after 30 years as the Director of a small county department of social services, and I had to deal with boards and local governments and state administrations, and, and I’ve always been- had some conflict where Bowen Theory has been helpful.

Schara: Can you say how? Can you say how it helped you? What’s the one or two principles or methods, or what were you

Combs: Most of all, it- when you have some understanding of emotional process and, also, the need to self-regulate, you simply do not get as upset by the nutty stuff that other people do, and also the things that I do, when I’m anxious. And after all, even if I took a positive stand, took positive stands on stuff, I would, in the process, get anxious and often do things that would be inappropriate and therefore tend to validate those who would criticize me. But I did less of- much less of it than I would have.

And I also was always able to stay in contact, pretty much, with people who were very actively in conflict with me. And I, I’ve had boards, board of directors in my county, that tried to have me removed, and I had to go into a grievance session against them, and I chose to defend myself rather than to have a representative, mainly because I- I was reasonably confident that I could do it without getting too reactive. Whereas I thought an attorney, or agent would get highly reactive and attack.

And I was able to do that and survive that process, and come back and work with the board, after they lost.

And they weren’t happy, of course. They didn’t love me, but they were able to work with me.

And I was also able to work with local government. And I had a situation where I had a closed session meeting with local county commissioners, with nobody present but me and them, and told them that if they wanted me to go I would quietly go, but if they wanted me to stay, to get some new board members that did what they, the commissioners, said they wanted me to do. They said they wanted me to do certain things, and then they would get- appoint board members who wanted me to do something different.

And so I told them, and I was able to do that and still retain- I was able to do that and retain a certain degree of- of detachment. I didn’t get angry at the commissioners, or my board members. Some of them, the board members, were furious with me,

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: but I didn’t very, very angry at them. And I mean that. And, and that’s where the theory has helped me, probably most. And the same, when I was a supervisor, before I became a director.

I was a supervisor, in foster care, and I had an evaluation system that was very factual [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: a report of this system and how I used it was published in May-June, 1979 issue of Children Today], and I had conflict because of that. And, again, I was able to, to keep working with these people and not take them so seriously. And, in fact, have good relationship later, after I was no longer there, they like me now, you know, But not necessarily while I was there. And that’s Bowen Theory. And I would make, occasionally, these presentations, about this stuff, too, at the Wednesday theory meeting.

Schara: And that’s you- would you call that self-regulation?

Combs: Oh, I-

Schara: That not taking the emotional clues, and then being caught in this reactive spiral?

Combs: Well, yes, being able to self-regulate, in other words, not getting too angry at them. I’d get angry, but not too angry. And I would’ve never been able to do that without having an idea of Bowen Theory.

And I’ve had those problems, I used to ask people, many of the people we both know, that worked in the agencies–one of the standard questions I would ask would be, “Have you had conflict, with how do you avoid. . . .?” I used to look for clues.

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: Maybe I’m doing something that’s just wrong! How can I avoid having this conflict? And it was partly me, my problem, of course I was having some part in it. But again they were all clinicians.

And I think that you can avoid much of that as a clinician. I did have a, a colleague, or member of the theory meeting, that we both know well, call me in the 1980’s. She was having a problem; she was a clinician, but in a public agency. And she was having a problem and, and I told her I was just so happy to hear that. [laughter]

Schara: [laugher]

Combs: I said, after all these years, finally there was someone that was having a problem besides me! ‘Course I wasn’t able to help her. [laughter] But I was-

Schara: Well, you might have helped her stand on her own two feet [laughter]

Combs: But I- But I was tickled to death to find that there was somebody else that was having a problem. So, that’s how Bowen Theory just helped me, in lots of ways, but in that one way. It’s been a great help. I had probably the most serious crisis that I ever had in my department. It was an embezzlement, a serious embezzlement by a trusted employee that I highly valued and had hired. And, and I saw that as a major defect, as the most important major defect of my administrative experience. I saw me playing a part in that process, and Bowen Theory, again, helped me deal with that, be more tolerant of my own shortcomings, you know.

The board stuff I didn’t see as something- I saw that as a, as an effect of my more responsible behavior. But the embezzlement was a real morale jolt, and Bowen Theory helped me get through that. Again, I presented that at the Wednesday theory meeting, that experience.

Schara: Did Bowen say anything to you about it, that you can recall, that made a difference?

Combs: No, not much. He asked for a few facts, how much, I told him, but most of all– I can remember one meeting that I attended, during that period, I made a presentation, and I was awfully tense. Not because of the presentation, just generally tensed-up. And he made some ridiculous comment, [laughter] I cannot remember what it was, it was something about chickens,

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: and it got me laughing so hard, I just, I simply lost control, I laughed. I just laughed uncontrollably. He just was so good at that, you know?

Schara: What would you call that? Interrupting your anxieties?

Combs: Ah, it’s detachment.

Schara: He was detached enough-

Combs: So detached from the, from my process,

Schara: That he could relate to you, he was so detached! [laughter]

Combs: Well, when I turned and looked he had a smile on his face. [laughter] And that was, you know, he could do that. He could, he could make some comment, that would defuse, lower anxiety, better than anybody. Nobody comes close to that, that I’ve seen. And so, anyway, that’s a little bit of my experience with how the Theory has helped me.

Schara: Yeah, that’s, that’s pretty interesting, the way in which he was able to take a reading on people, and somehow, kind of leave you with the problem that you had. But give you a feeling, kind of, that that problem wasn’t something that you couldn’t overcome. And it wasn’t a big deal.

Combs: I-I hear that. Yes, that’s right, it was my problem, but, hey, it

Schara: [laughter] It’s not that big of a deal.

Combs: was, it was my problem, and that was that. You didn’t- he wasn’t in any way consoling, and . . . .

Schara: Maybe the opposite, but he had a way to- somehow or another, I think the other thing is that it activates your self in it, that you’re- that whatever that comment was, you start uncontrollably laughing, kind of diminishing the importance of the problem, and somehow or another your intellect is able to take a more objective view of it, which sets part of you free. That’s how I would put it.

Combs: Well yes, something like that, yes. It did. I would- even in my most difficult times and during this, again, I maintained a sort of a detached systems view of this process. And we got, the whole department, we got through it. And it was hard, because everybody knew this person and liked him.

And, and so it was hard on everyone. But we all got- we got through this process, and part of it was, being able to be to, to, see this in systems terms. Things had been going, in my mind, so well in terms of actual agency performance. Because I, I’ve always been a zealot on keeping factual information about performance, on monitoring it. When I supervised foster care, I did that. With-with foster children. What was going on with them, factually. And I did the same thing in my department. And, and I was so pleased with what was going on, how we were doing. And, and this was, that’s why this was a particular jolt. Because I had been doing so well, and wham! out of nowhere, this embezzlement came, so. it was hard. But, again, the theory gives you understanding and perspective.

And also, by that time, I had been involved with Bowen Theory for about, oh, twelve years or more. And, and when you’re involved with the theory over time, you experience the ebb and flow of functional change that comes about. Most of the people, and I know from my experience with the theory, initially experience a great functional shift. Once I started applying it, thinking about it, and applying it in my family of origin, I noticed the improvement in functioning. My improvement in functioning. lasted several years. And, and then you go through a, a, period, where you ebb. You don’t go back to original functioning, but you generally ebb, at least in my case, and in the mid-70s, I had sort of an ebb, and I went, I saw Dr. Bowen several times for personal consultation. During that time, I got to know him a little bit better in another way, and that was beneficial. But I didn’t get much that I didn’t already know. I, I have always been a- I thought that, that I knew the information. I had attended the theory meetings regularly.

I knew Bowen Theory, I didn’t need somebody to tell me what I needed to do. I knew what my short- comings were, knew what I needed to do. But, still it was helpful having him look at my family, and, and getting an understanding of it and having some of his thinking. But, anyway, by the time I had this embezzlement, I had gone through at least two or three of these ebbs and flows, you know you just, you have these damn periods,

Schara: [laughter] Yeah.

Combs: and, you know, you get through them. And if you can get through them, you can regain functioning. My guess is that anybody who has stayed with the theory for a long time has had some variation of this experience. And I, I think the overall move is clearly up. I think there’s no question In my mind, that over decades my functioning has improved. But, as I say, it’s been these ebbs and flows. And, and during this embezzlement I saw it as just another, you know, major challenge that a person has to handle. And so, this gave me perspective, too.

Schara: Do you think that your work with your family of origin, I know Dr. Bowen talked about differentiation of self, in a triangle. That you couldn’t differentiate a self outside of a triangle. And that you somehow had to put these other people together and get you out. And that was sort of the rough, the rough idea, of separating a more mature self, from the way in which the organization, or the family, would try and control you. And not consciously, even, but just the way that they do it. The way systems function.

Combs: I, uh, yes, of course, anyone who, who wants to make progress, that is, to improve functioning, has to go back to family of origin. I mean that’s because, as I’ve said, that’s where the action is’ that’s where you have to, where you have to go. I, and I did, I did a lot of that– de-triangling is what I think leads to that initial, functional shift But, but de-triangling, I’ve always seen, is just the first step. Our functioning, our basic selves, is built on all these internal neuronal structures and connections that have to be made. And, and, getting free, de-triangling frees you up,

Schara: Mmhmm. [laughter]

Combs: but it doesn’t create any new . . . [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: structural organic foundation]. You’ve got to do that through behavior, taking stands and trying to be responsible over time, and it, just it’s a slow process. But I think that leads to change. Yes, I did do that. And- and I did, ah, my, my family of origin had noticeable improvement. I have- I had an older, bachelor brother, who [laughter] who probably- no one better defined the term ‘confirmed bachelor’ than he did. And, and, in, in the late ’70s, he suddenly found a lovely woman, and married and had a family within a few years.

Schara: [laughter] Wow.

Combs: You know, another brother did the same thing, variation of that. And these . . .

Schara: Without your mother dying?

Combs: Without– in fact, my mother’s improvement–that’s the other story. My mother, who’d always been the symptomatic one, the most symptomatic one, in our family, improved functioning dramatically in the ’70s. I have pictures of her and you can just see, from the pictures, how different she was from the early ’70s to the late ’70s. And my mother, a little background on my extended family, family of origin: I’m the second of five, older brother, younger brother, younger sister, and a younger brother who’s really an only– he’s ten years younger than my sister. And my grandmother lived with us. My grandmother was an oldest of five sisters,

Schara: Your mother’s mother? Or-

Combs: Mother’s mother.

Schara: Mother’s mother, ok.

Combs: A real piece of work.

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: Oldest of five sisters, and my mother was the youngest. Of four. And she was born when my grandmother, her mother, was in her mid-forties. And she was always the baby of the family, pretty functional; she was not the- the dysfunctional one, she had an older brother who was the one that got more of it [the intensity] than anyone. But, she was also– she did graduate college– always very dependent. Her dad died when, when she was about thirteen. And her mother pretty much raised her, alone, and they were of course [laughter] tightly

Schara: Constrained.

Combs: fused. And my, my grandmother- in fact, when my dad asked my grandmother, for her daughter’s hand in marriage, my grandmother said, her response was, “What about me?”

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: [laughter] And of course my dad intuitively knew, he was very much in love, and he intuitively knew the right answer to that: “You can live with us.” [laughter]

Schara: [laughter] “You can come and live with us.”

Combs: And so, about a year or a year and a half after they married, she moved in. And stayed in. And it was for most of the time she lived- for my- she lived with us up to my age fifteen. She died when I was fifteen. And for most of that period, about twelve years, it was reasonably quiet and calm. My mother, and my grandmother got along very well. And, it was, and my mother really didn’t become symptomatic, that is, have- start drinking, and binge drinking, not drinking every day, ‘til when my grandmother got the first cancer diagnosis, two or three years before her death, and following her death, my mother drank, and was frequently inebriated, and, and again I-I- and Bowen Theory helped me understand that process. Even when it was going on– one of the questions you asked: what was going on in my family that tended, tended, to spawn interest in Bowen Theory?

And, and it was- when I was a teenager, I- my older brother and I were closer in age than to my younger brother and sister. And we would talk occasionally. And I was surprised, as a teenager, to find how different his view of the family and the people in it than my view. He, he saw my grandmother, who was a very bossy, domineering woman, in much more negative way than I. For instance, she was always telling me what to do, and I just ignored her, never paid any attention to her. But I liked her. and, and she would, in fact, always- she was never was one to ask for any-anyone to do anything, but she would always ask me to do stuff. She liked me too, obviously. We got along just fine, and she would say “Do this or that,” and I would just– if I didn’t want to, I didn’t do it.

And I never thought twice about the- saying no. And apparently, my brother- I just realized, as a teen, that he had such a different view of her. He took her much more seriously than I did.

Schara: This was your older brother? [laughter]

Combs: Older brother. And would kind of fit with Toman [Addendum J.J.Combs, April 2017: Walter Toman] And his sibling stuff. And, and his view of my mother was also- even as a teenager I saw my mother’s symptoms as somehow tied up in a systems way, I did not see her as just the, the symptomatic one, I did not have such a static view of her as the symptomatic person. And the low level person. It was different than his, you know, his was very, very cause-effect, very judgmental, and so it was a different type of view. I’ve- I’ve heard, that people who are attracted to Bowen Theory are generally persons who grow up in sort of an intense family situation, and they’re a little bit on the outside, of it, and, and that they tend to- but I don’t know . . . .

Schara: It makes sense though, in a way, that you’re a better observer. You’re not the direct focus of things, and you don’t have as much conflict, and you have the ability to step out outside of it, because you’re not as caught up with it. But certainly that whole ability to be an observer, to me anyway, it represents how- whether or not people can actually use Bowen Theory, and see their own family. As part of evolution, so to speak. [laughter] You know? And not take everything so personally. But I do, I do (I’ve read), also, that family therapists are often- have a sibling that’s been hospitalized. And, and so they’re a little outside and they can do something, maybe, about it, to manage themselves. So, the one of the questions in this was the- “Did you have insights into where Bowen picked up his ideas fueling his research?

Combs: As a matter of fact, I do have something I’ve often thought played a part, an important component, that’s underappreciated. And that is his experience in growing up in a small town, with a stable population going back over generations. You know, there’s nothing like it. I had a similar experience, I grew up on a small town, the county seat just as his was, of about, oh, 12-1400 people. And very stable populations, and I could- many of whom, in my case, I’m related to.

And, and you can go back and look, and track, families over the generations. And see, you see how they turn out. You just grow up with that stuff. And you see the, the suicides, and the, and the addictions, and all the other symptoms that, that some have, and some are more functional. And are– I know a large family of sixteen, that really runs the spectrum of functioning. And you can just see it so clearly. And I believe, that that helps, you just grow up seeing that and getting a base.

Now the other thing, I think, that’s- might have been very important, in his, in his forming a basis. Obviously Murray Bowen was Murray Bowen, and he came out of his family with a unique head; but the experience of the small town and the funeral home business– there is nothing like that business. When I saw Dr. Bowen, for consultation, he made mention once, he said his dad was the mayor of the town, I believe, and that his dad

Schara: Yes, he

Combs: knew everybody in the county, or, if he didn’t know somebody, he knew who his parents were. He could look at him and tell him who his parents were.

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: And I told, made mention, I think, to him, that “I hear that,” because I had had a close friend as a teenager, who went to work for the funeral home. And he told me, my friend, that, he said, “I thought I knew the county well before I started working for the funeral home.” He said, “I didn’t have any idea about (all these) things, all the stuff that goes on in the county, and the county.” And I think having that experience– not only are you seeing families in intense situations, all the time, but- but you’re seeing, you’re getting knowledge of the community, all of the ties and the inner relationships of the community in a way that you cannot in any other business, and, and my guess is, his, his family business, handled the great bulk of funerals in the county, because

The funeral home that my friend worked on did the same, usually.

Schara: [sound of tape switching over] We’re going to start again.

Unnamed Speaker: The family home that your friend worked at…

Combs: The- the family- the funeral home that my friend worked at also handled most of the funerals. Usually, you have maybe two or three funeral homes in a county, but one will handle the bulk of the business, and this one probably did too, and my guess is that he just knew. Also, up until the ’50s, and probably even the early ’60s, in rural- most rural communities, the funeral home provided the rescue squad service. And, and I’m sure it did to some degree when Murray Bowen was a

Schara: Right.

Combs: Mm. youngster, he- it was in the ’20s, or 30’s, and so it was probably a lot more limited. But again, you see, you gain experience, intense experience.

One of the experiences he mentions that really affected him, was the one where he picked up the teenage girl, went to Nashville, and, she was alive,

Schara: Yeah, that’s right. Went in the ambulance.

Combs: functioning, and a few hours later was dead; and what, what really struck him was the inability and the hand-wringing and the perplexed attitude of all the experts, who were just unable to do anything. And all of these, these types of experiences, I think, just had a real impact, in terms of the forming a basis for the theory, and the generational aspect of it, of the functioning. And . . .

Schara: I remember that, (you) said he, he knew he could make a difference in medicine. Because there were a lot of things that people didn’t know. [laughter]

Combs: I- those types of experiences, are, are, I think, you know, Ulysses- let’s just digress a moment- Ulysses Grant, in his first battle, he was terrified, went over the hill, I believe, with his forces, and he was just frightened, almost immobilized by fear, and they got over the hill and he looked down, and the other general had been so fearful he had run away, they had retreated. And the realization hit him, that “Hey, he was just as scared and immobilized and ineffective as I, as I was.”

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: And just having those types of realizations lead one to say “Hey, we got- we need, you know, there’s got to be a theory, something- we need a new something.”

Schara: So that was one of the questions, is “What-what was the main contribution that Bowen made, to Western scientific worldview.”

Combs: [laughter]

Schara: Because, like you said, especially in psychiatry, it wasn’t, there was no science, that’s there. And to some extent, I suppose, maybe drugs took over, in away, because you could claim to do science, we could tell, “This one does better on the drugs and this one doesn’t.” But with therapy, it’s… [laughter]

Combs: Well, yes, I mean it’s- you can look at that question in a number of ways. I look at it- I’ve thought about it more broadly, I think that, that what he- his contribution, more than, in its most basic in a most basic sense, is, it- he- he has- he puts man in nature. And, ah, man is, man needs to see himself as part of nature. . . .so he, he can adapt to, to the environment. Instead of control it. Now, and we hear that- yesterday, at the- at the conference, we heard Pat Comella talk, but- but what I’m thinking of is something deep, you know? It’s a major shift. And, it’s such a basic one, that- that people might say, “Yes, of course, that’s-” but, but “that’s the case, we have to do that.” But- but it’s putting man in nature, and, and then using science to try to understand man and, understand himself. And, and, and enhance self-regulation. And- Instead of having this top-down, control. We think- we think that- we think that we , if we can only get, the, the, the correct policy, and we can get the right pe- leaders in, and, and, that’ we’re going to have, we’re going to improve. And we may do that, momentarily, but we’re going to have, what Dr. Bowen described as a major societal crisis- crises, until we- we have this, over the generations develop this self-regulation, that we do not have now. And his theory is a roadmap to doing that, it’s a way of placing man in nature and understanding man. And for man to understand himself.

[Addendum, J. J. Combs, April, 2017: What I’m trying to get across above is that I think an essential step in moving human behavior to a science is the acceptance of man as just another species, ultra-smart, but with an emotional system he shares with other animals. Then we’ll be able to look more objectively at the interaction between the cortical and subcortical processes that make up human behavior and how the process of differentiation occurs within a family relationship system. A view of man as special and unique obstructs this process. I think Bowen recognized this before he began his NIMH research. And I believe he had an understanding of the emotional system and differentiation before he began seeing the family relationship system and began to develop the concepts.]

Combs: And, and that I see as his major- and that’s kind of a hazy answer. It isn’t like- it isn’t, you know, the theory, and doing therapy, and all of that. It’s something very basic, I think. And I think that, that makes him, in my mind, one of the most original thinkers, at least in the last century. [Addendum, J.J. Combs, April 2017: I’ve always seen Bowen Theory broadly, as a theory of human behavior that expands human consciousness.]

I really do think that he- I really can’t think of anyone, who’s more original than he wa- than he has been, in, in developing, that theory.

Schara: Well doesn’t his, his research, or his, and his therapy, enable people to see their own family as part of nature, and their own ability, to, to be caught up with it, as part of nature? And maybe it even allows you to see the variation, I don’t know for sure, but I think if you stick with it long enough, and you see enough families, you, you see the variation in nature’s ability to try to enable families to, to manage anxiety- to, some of them can self-regulate, as Bowen used to say, many of us grow up on the backs of schizophrenics, and the process goes on and on. But some can actually get out of that, and be able to influence that, entire system, to become more mature. Which is part of nature. I th- I don’t know, I’m just saying, I think that, like, psychoanalysis shows a different side of man that’s maybe, not so much a part of nature. That’s formed more by culture, let’s say. And not such a natural system.

Combs: I, I hear what you’re saying, and, and yes, I don’t dispute that, that theory does, it does, enable those things. Lots of people take the theory, and they use it to the degree that they can, or want to. And some, you know, they- to me, they’ll be only a part-way into the theory, but they’ve gotten a lot of benefit from the part that they use. Some people use, to me, they use the theory without variation of self, or differentiation or multigenerational transmission, or- but they’ll just use the systems [part], the reciprocal functioning, the triangles, the projection process. They’ll see that more, and they may just use part of it. But they benefit from it. And, you know, they get something out of it. [Addendum, J. J. Combs, April 2017: What I’m trying to get across is that I see the concepts of the emotional system, differentiation and multigenerational transmission as anchoring Bowen Theory in evolutionary process, which allows a “natural systems” rather than just a “systems” understanding and moves away from a blaming or power focus, not just in the family but also on a societal level.]

Combs: I remember an article that was written in some publication around the time of his death, some woman who mentioned- who said she was a “Bowenian feminist, “

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: she said, and she said it with humor. She said that he [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: Bowen] always- he kidded her, or you know,

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: she kidded him about it. But you have people like that, and, but she got something out of the theory, she was genuinely moved by her personal contact with Bowen, but also, she got some benefit from the theory, and application to her own family.

But, obviously I wouldn’t say she bought into all the theory, or certain parts of it. So, yes, I think that people use it to varying degrees. I do think, though, what I’m talking about, is something that’s going to be over the generations, and we’re a long way, from, from- I think, implementing or gaining [ Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: acceptance of the Theory]. It’ll take generations of, of experience and struggle to get the, the self-regulation that we, we need, and a theory provides a valuable guide to, to the effort, but it will be a long struggle. And, I do not see us gaining the necessary cortical control, over subcortical processes, that we need to have. Except through generations of struggle, with a lot of misery as a motivator.

And I’ve often used in presentations the shift to science in the seventeenth century. And I see that as a major move, but I see the motivator as all the misery that was going on then. Up until that time, and especially the infectious disease–in the fourteenth century, fifty- around fifty percent of the population, around most of the world, probably, although in China and India not so much is known; but in the, in the middle east, and, and western countries , from forty to sixty percent of the population died.

Schara: Wow.

Combs: Can you just imagine, that, us dealing with that sort of…?

Schara: No.

Combs: It’s almost impossible- to comprehend.

Schara: Yeah.

Combs: And, in a three year period, this happened. And you had tremendous misery. And, and then for centuries the plague would hit, and even as late as the mid-seventeenth century, the 1660s, London lost twenty percent of its population to the plague, 100,000 people. And again, we had all that misery and all the wars, and the lifespan, I think for the nobility, was around 30 years. And you just had misery. And man, shifted to science, I think, the shift to science, away from a more static view of the environment. But [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: man] needed pain as a motivator. [laughter] And,

Schara: [laughter] Or he got pain.

Combs: And I think that we’ll need a similar type of pain and misery, to motivate us to make this next shift, which will be just as much, just as major a shift, as the one to science. . . . .

Schara: Sort of a Malthusian view of the world, is it?

Combs: Well no, not really. Perhaps. Malthus, was, he had kind of a dynamic view,

Schara: He did, yeah.

Combs: Not static. But no, I think- I see it as a challenge, and it’s a challenge that we met before, and we can meet again. And- but, we’ll need misery as a motivator, to, to meet the challenge.

Schara: So when you talk about the subcortical view, of, mankind has a subcortical part of himself, that resists self-regulation, putting off problems into the future somewhere, and we’ll deal with it, and, yeah [laughter].

Combs: Sure, hey, look around us [laughter]

Schara: And that’s, that’s kind of the major- when you’re talking about the subcortical view, it’s that inability to take responsibility, for the future. Put things off into the future. Something like that, is what you’re talking about. And the self-regulation, would be a more factual view, of the world, that allows you to regulate yourself to make better decisions that are not based on a subcortical, kind of, I want- I want what I want now, you know, and I don’t give a damn about the future so to speak.

Combs: Short term thinking is, essentially, a subcortical [process]. It isn’t always wrong, acting subcortically, you know, short-term, but it, but it, it’s a short-term [process] generally. I see it as a sub-cortically driven process [emotional process]. . . .

Schara: Yeah

Combs: [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: subcortically] dominant. All our, probably, all our processes are subcortically-driven, but it’s a – it’s [whether they’re subcortically] dominant [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: that determines if they can be seen as emotional process]. And, I would see that as a, as a short-term. And we think short term. And we’re reluctant to, to implement things that would help us. Again, in regard to Bowen Theory, for example, Dr. Bowen, he published his first paper, in the 19- late ’50s, I believe, and his experiences with families at NIMH showed a way of looking at families that just opened up enormous research. It was an entirely different way of looking at families and understanding behavior. And how much is that- it’s been two generations now, and we [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: society] haven’t really done anything, with it. It’s still–the Bowen network, is still, to me, kind of isolated, out there. You know, it’s easy to get the impression when you’re around people who think . . [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: theory] that the theory’s more prevalent, than it is, but . . .

Schara: Yeah. Well, that’s why I put in the thing about, about the drugs, because back in the NIH, they had the different people, that were doing research, and one of them was Lyman Wynne, and one of them was Bowen, and the, the director of NIH, would complain that the Bowen group wasn’t producing any papers. And no results, really. And they were just observing. And, the Lyman Wynne produced a lot of papers.

Combs: [laughter]

Schara: And, they got into the pharmaceutical things, around that time, so I think the government gave three million dollars, something like that, to research the family. Because the family was the factory of democracy, and it was producing schizophrenics, and how does this happen, and what can we do about it. But when they landed into the pharmaceutical world, there, in the ’50s, science proved that that can help. [laughter] And it’s a l- you know, you need a longer view of the family, to see that Bowen Theory is making a significant difference. In the ability of people to function, whether it’s higher level people coming back to help the lower functioning people in a way that’s not intrusive and not controlling and not blaming. But, anyway, that’s what I was thinking about extending or refining the theory, that as you said, that he developed ideas that that haven’t made it into, I don’t know if I want to say the popular press, or into people’s imagination, even, that how this theory could enable people to function at higher levels.

Combs: I-I don’t see Bowen Theory being implemented . . . [soon]. I think. . . that Bowen Theory . . . requires a different belief system, and belief systems are very, very basic–very difficult to change. The great ones, the great religions, they last for centuries because they-they improve adaptability. But- but they kind of- come out of a man’s head, and they lead to-to cul-de-sacs, as we’re now finding ourselves– we see ourselves as special, as unique, and again I believe [our belief] systems say that we’re- we’re unique. They don’t see us as just another species, with similar biological constraints. They-they see us as, as different. So, giving up that is an enormous sacrifice. It is, it is something– again, if you, if you make a shift with a cause-effect mentality, it is a very painful experience, because families, for example, . . . raise their children, they love them, they try to do well, and some turn out, some kill themselves, some addicted, they do all sorts of embarrassing things; and the pain of a conventional view, that holds responsibility for parents . . . would just be so great. In the past few weeks, I’ve attended several funerals, one- -the pain, if they thought- if they used the information part of Bowen Theory, in a conventional mentality, it would just be awfully painful. You can understand the resistance . . .Involved in a shift. It takes a [different] view of seeing symptoms– as not the person–and that’s. . . a very difficult shift to make. And it will, I think, only be made– it’s a belief system shift, and it will be only made under duress, which gets me back to the misery part, again. You know. We have all sorts of [societal problems] We need fewer people, and although I don’t believe in conventional approaches to reducing population, necessarily, but we need fewer people on the planet. And, I don’t know of any species that’s multiplied so fast than humans without crashing. And, you know, if you just look at it objectively, you just look at it and say, “How can we not, if we were a species, how can we not crash?” So, maybe we’ll have to crash, and, and Bowen Theory will be there for us then. And, and it will be there if it works better. I think it works better, I think it enhances adaptability.

And I thought, that will be the strength of it, you know. You can talk about it [a gradual shift to Bowen Theory through reason]. Everyone talks about somehow getting good research, and convincing others [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: through evidence/facts]. I don’t think [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: that’ll work]. I think it’s fine to do that, to try to do that, but I don’t think it will matter much. What will matter is if it really helps enhance adaptability, and we have the, the misery as a motivator. Then I think, that then it’ll be seen as [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: an effective option].

Schara: Well that might be, pretty accurate in terms of the way that it started, in which people who were miserable, and who could see the misery in their family, had something to do with them. We’re willing to take back some of the misery that was being focused on others. And, and in, as a result of that, the family itself, was able to rise up, and people became more adaptable. It was a small number of people who were willing to do it, and it may be that there are a small number of people who survive the misery, whatever it is, if it comes to be.

Combs: Well, it doesn’t take many– it takes a small number, during the seventeenth century– I’ve recently, in the last year or two, read a book by Edward (Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: Dolnick), who pointed out that it was a small number of these people, these scientists– hell, Newton. . . had very few colleagues that even understood what he was doing. And it’s, it’s the commitment and motivation of the population to seek some improvement, and then they’ll take leadership. And Bowen Theory provides a really important understanding of functional change because we’ll always have variation in the level of self.

Schara: Right. [laughter]

Combs: . . . even if we meet this challenge and break through and have a more regulated society it will not be utopia. Human beings will always be a challenge, you have this variation. And I there are ways of, I think, having environments that- that promote functional self, and promote change. [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April, 2017: I think Bowen Theory’s understanding of functional behavior and how to promote it has special value on a societal level.]

Schara: Yeah.

Combs: You know, man, now, does not know how to do that.[very well]. In the past he’s controlled, functional and basic level of differentiation by doing all sorts of things, everything from slavery to genocide, to segregation, to-to- all these ways of keeping people down in a static sort of way. And we need to do what our, what a functional family does, which is: you have these youngsters, that are less functional, and they grow up.

And all the time, you try to respond to their particular developmental need, if you were doing a [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: decent job] of course, we’re only partially successful at [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: it], but if you did you try to do that. We need some variation of that, where people who are less functional can over the generations [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: raise basic self]. And we did a pretty good job in this country, for a long time, doing that [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: comparatively]. Better than any in history, really, at the- at doing just that, allowing people to change, to improve self over generations. And we need something like that.

Schara: Yeah, maybe Bowen Theory will at least point us in that direction. I’m reminded of- we’ve gone a, gone a little bit over an hour. Is there anything else that you wanted to put in? That you can think of here? That- Any-

Combs: I’ve been rambling on! [laughter]

Schara: [laughter] I think you’re pretty coherent here. [laughter] You’ve got a thesis. [laughter] Yeah. [laughter]

Combs: Well, trying to remember kind of [Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: stirs me up] enough anyway. Good for me. My standards.

Schara: Alright, Jay, thank you very much, I enjoyed the time with you, it was a pleasure to get to sit down and talk with you, cause we kind of pass in the hall, and don’t get a chance to get-

Combs: Well, I’ve always (Addendum, J.J.Combs, April 2017: thought) hey, I-I-I’ve told Kathy (Vlahos) and other people, I was the director of an agency, and, and I always loved people who could do things, and I, hey, I

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: directors are helpless, and I’ve always valued people who could- I always said, (Punkin) can do things.

Schara: [laughter]

Combs: You know? [laughter] And I like people who do things.

Schara: Thank you. [laughter] Well, thank you very much. Really appreciate that. It’s a- that is my middle name.

Combs: My guess is, that Bowen did too. Andrea, he valued people who could do things.

Schara: Yeah, I think- yeah. I think so. I think he saw that in me. Thank you for that.